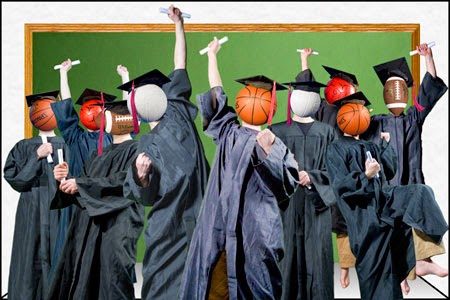

Opportunities in life come in all forms. For young athletes

who aspire to go to college and receive an education, no better opportunity can

come than that of an athletic scholarship.

While schooling is considered the best and most productive

way to prepare a young person for the rigors of adult life, the cost of attending

college can reach six figures.

For those who excel in sports—and in the classroom, the

price tag for a college degree can decrease significantly if the student

chooses to put in the hard work required to compete in their sport at a higher

level.

In today’s ultra-competitive society, finding these types of

opportunities can be difficult. That adds a third element to a young student

athlete’s preparation during his or her prep years: getting themselves on the

recruiting landscape.

But how does that happen? When and how will college coaches

take notice of your child’s athletic skills? When does a top performer on the

field and in school begin to think seriously about getting a college scholarship?

The answers vary depending on the sport and the region the

student plays in. The days of a college coach showing up on the sidelines with

a scholarship in hand are long gone—and only really ever existed in extreme

circumstances, or in the movies. It is now up to the student athlete and their

parents only, to get educated on the

complicated processes involving recruiting for an athletic scholarship. So, if

the goal to seek such an opportunity is determined early then the answer is

right then and there.

Parents begin exposing their children to organized sports as

early as four years old. It starts with local park and recreation activities

and often moves into accelerated leagues that compete all across the nation. As

the child grows, the time and money invested by the families goes into the tens

of thousands of dollars.

There are team fees and high costs for the best equipment.

There are personal instructors, trainers, nutritionists and often doctors or

physical therapists. Travel ball expenses including fees, hotels, fuel and food

quickly mount up. For something that begins merely for fun, it can quickly turn

into a life-altering commitment.

This level of competition is not always just the child

wanting to play either. Frequently, this involvement is driven by mom and dad.

Kids can be serious competitors, but they do it for fun.

They love to play the sports they’ve been involved with since being very young

and they enjoy being with their friends. Parents do it for control.

Sometimes it’s a case of the mother or father living

vicariously through their child, attempting to create something that they may

or may not have experienced during their own youth. Many times it’s as simple

as the parents wanting their child to experience the camaraderie and safety of

being involved in a positive group setting. The reasons are many and differ

from family to family. One thing is for certain, however, expressed or not, the

ultimate dream would be to receive a full athletic college scholarship once

this road has been traveled.

What doting father, who has spent years coaching, taking

time off from work, coming up with funds to travel weekend after weekend, would

not fight back tears of pride if his son or daughter were to achieve such a

pinnacle? Not many.

The disheartening part of all this hard work can be when it

amounts to nothing beyond the fine memories. That might be good enough for

some, but not for most.

Often there is a time of realization as a young athlete

grows older and faces tougher competition that he or she is just not good

enough to go on. That happens. It is the parent’s duty at that point to

recognize the end may be near in their kid’s sports endeavors and simply enjoy

the moments of watching them participate as they come to a close.

Then there are the ones who are good enough--the kids who

are the best players on their teams. The ones who everyone talks about season

after season and proudly says, “she’s going to play in college someday.” But

will she? Will that opportunity ever come?

If that player or her parents have not taken any steps

beyond just competing on the field as their way to get recruited, then the chances

are no.

Just playing on a travel ball team and participating in top

tournaments in your region, is not enough. That, simply stated, is just the

beginning. It is necessary for development as a future college athlete, but it

will not get a student recruited for an athletic scholarship. Next time you

attend one of those types of tournament events in your child’s sport, take a

look around. Behind every set-up of lawn chairs and coolers, is a parent, or

parents, grinding their teeth and sweating bullets because their child is going

to be a senior and has yet to receive a call from a college.

This is important to digest. Only such a call—or email, or even direct contact from a college

coach who handles the recruiting for his or her team, is the indicator that

your son or daughter is being recruited. Not

the friendly and positive “coach-speak” most will hear at the close of a

college camp that the parent paid for, for their child to attend.

The competition for athletic scholarships in college is

intense. There is no shortage of worthy athletes. Depending on the sport,

schools only have an allotted amount of scholarships to give with hundreds, and

even thousands of qualified kids wanting those scholarships.

The larger Division 1 universities, such as the schools in

the PAC 12, SEC, or powerful independents like BYU and Notre Dame, hold most of

the cards when it comes to recruiting. Because of the high exposure of these

schools, they are the most desirable for the serious student athlete. These

institutions have the budget to use the most effective recruiting techniques,

such as having full-time recruiting coordinators or the use of the latest

software to weed through the thousands of prospects to locate the ones who fit

their needs.

Many things come into play for these coaches, from the

academic standing of the athlete, to the year they will be available, to the

position they play on the court or field.

These types of requisites are often broken down by a staff

of coaches to identify the top few who will get the chance to visit the school

and perhaps offered a scholarship by the head coach.

The smaller schools don’t have these luxuries in some cases

and must rely on outside sources such as scouting bureaus, or camps to find

prospects they can actually have a shot at attaining.

Standing in the shoes of a smaller college coach, finding

the best student athlete for their program--that they can afford, can be a

daunting task. They often recruit the blue-chip athlete, but lose out to the

bigger schools. Their recruiting boards, for this reason alone, must be much

deeper.

A major misconception with the smaller schools, and these

are the Division II, Division III or NAIA institutions, is that they do not

have the academic or athletic standards of the DI schools. This is not true.

While the number of scholarships may be fewer, the product

on the field can be as, if not better than, some DI competition. And let’s not

overlook the main reason for going to college… the education. If a D3 or NAIA

school is strong in a young person’s chosen field of study, and competes at a

high level in their conference athletics, then how could one turn their nose up

to such an opportunity? Especially since USC has yet to call.